Chilean Telexes

and the Allocation Problem

![]()

Or, “How to Get Britain Moving Again.”

Written for the TxP Progress Prize., an essay contest in partnership with Civic Future and New Statesman Spotlight. In the spirit of the competition, I’ve explored a solution to resource allocation which goes against my economic instincts, but which has at its core a capable state apparatus that harnesses and democratises cutting-edge technology. I agree entirely with TxP that the apparent depth and entrenchment of certain societal problems do not make a solution any less viable - as long as we fully exploit the possibilities afforded to us by science and technology, and don’t wallow in despair!

The sky is blue, the youngest generation is lazy, and Britain has a productivity problem. In the years since the financial crisis, we’ve had a steady stream of policy efforts motivated by this problem. These ranged from anaemic (Rishi Sunak’s half-hearted levelling-up strategy) to disastrous (did someone say rotting lettuce?). Yet productivity has grown by just 1.7% during this period. This has cost the average British worker £10,700 per year in lost earnings and left us lagging conspicuously behind the US, Germany and France.

This is not for a lack of think pieces. There is cross-party consensus that low productivity is a problem. The Financial Times seems to run monthly stories on the issue. The Resolution Foundation and the LSE ran an inquiry and recently published the resulting economic strategy recommendations, including policy suggestions to fix education decline, the skills gap, lacklustre business investment, and gaping regional inequalities.

Though few would dispute this grim consensus on the productivity problem, I can’t help feeling that the widespread dissatisfaction amongst the British public comes from a more fundamental place. Eight out of ten Britons are dissatisfied with the way the government is running the country; the same proportion think “the world out there” will stay the same or get worse. Anxiety about the future and historic levels of distrust are hanging in the air.

And no wonder. Over the last 10 years, child poverty rates in Britain have increased more than in any other OECD country. 4.7 million tonnes of (still edible) food were wasted in 2022, yet 9 million households experience moderate or severe food insecurity: a shocking increase of 10% in 2 years. This points to a deeper problem with the way resources are distributed.

There is reason to believe the problem is too fundamental for policy tweaks to make much of a difference. For instance, some argue that the prevalence of low-skilled workers in the UK has stalled wage and productivity growth, and propose education policies aimed at tackling this so-called skills gap. But how can we improve educational outcomes if as many as 7% of pupils are malnourished?

To restart growth in wages and productivity, we should start by rethinking resource allocation. This is where Chilean telexes come in. In 1970, Salvador Allende’s democratic socialist government began an ill-fated attempt at computational economic planning. They used a type of Bayesian forecasting to make predictions based on production data and give the government “a bird’s-eye view of the economy.” “Interventors would use the telex machines at their enterprises to send production data to the telex machine located at the National Computer Corporation,” explains Eden Medina in *Cybernetic Revolutionaries. “*The computer ran statistical software programs that compared the new data with those collected previously. If the program encountered a variation, it would send the data over the telex network to the State Development Corporation (CORFO) and the interventors affected. As a result, CORFO would communicate with the interventors in order to help resolve the problem.”

Medina notes that their approach was surprisingly successful despite technical bottlenecks. During the sweeping 1972 strikes led by the opposition, “the government kept food supplies between 50 and 70 percent of the normal supply. It also maintained 90 percent of normal fuel distribution levels with only 65 percent of the tanker trucks in operation.” Later that year, a military coup brought down Allende’s government. Over the next two decades, the Cold War would draw to a close, and large-scale economic planning - no matter how digitised - would never reach the Western intellectual mainstream.

Even now, economic planning evokes Hayekian takes at best and memories of the Holodomor at worst. The Soviet command economy model has been objectively and completely invalidated by the humanitarian catastrophe it created. But planning does not have to mean centralisation. Remarkably, Allende and Hayek were in agreement that, in Hayek’s words, “the economic problem of society is mainly one of rapid adaptation to changes […] the ultimate decisions must be left to the people who are familiar with these circumstances.” Allende’s chief technologist, Anthony Stafford Beer, intended the computational planning system to maximise devolution and ensure that networks of workers spread across the country could collaborate on economic planning.

Advances in machine learning provide a strong technical case for revisiting decentralised economic planning. Deep learning algorithms are especially strong at constraint satisfaction problems, of which resource allocation problems are a subset. The private sector has already noticed. Traditional grocery stores have been pouring money into inventory management software, which uses state-of-the-art machine learning to predict demand, reduce waste, and track and streamline supply chains. At its core, the computational process is suspiciously similar to the tracking and forecasting of socialist Chile.

Ocado became the UK’s biggest tech company precisely by applying machine learning to resource allocation in the grocery industry. The Ocado Smart Platform uses customer demand forecasting to determine how much to order from suppliers. This planning approach has led to some seriously impressive reduction in food waste: Ocado wastes just 1 in 6000 produce items, a fraction of other major grocery retailers.

But the UK’s 9 million households in food insecurity are probably not buying their groceries from Ocado. This is where the government should step in. The simplest way to start would be government incentives to make it easier (and more appealing) for retailers to adopt inventory management software. For most grocery retailers, the technical barrier to entry is still too high - and for retailers that do have some type of inventory management software, it may not be explicitly aimed at sustainability or equitable resource distribution. A combined food waste/digital transformation fund could lower these barriers to entry, financially incentivise companies to cut food waste, and encourage digital management of partnerships with food banks and community organisations to ensure surplus food is properly redistributed.

A more ambitious idea could be for the government to take a more proactive role in gathering the data needed for economic planning and making it accessible. This could mean that redistribution of surplus food to vulnerable populations becomes a joint effort by the government and the private sector, which should make it less scrappy and more consistent. It could also bring together data from various companies’ sources to create a repository for wider demand.

In short, the goal of government involvement would be to harmonise standards for data-driven inventory management and food waste reduction across the grocery industry. Of course, there are still many questions about how exactly to implement this, how to avoid reducing competition, and how to improve the government’s own data management capabilities before it can effectively assist the private sector. But ultimately, we have the technology to dramatically reduce both hunger and food waste in the UK. What we need to do now is democratise it.

On being a failed

dropout founder

![]()

The dropout founder, while representing just 4% of unicorn founders, occupies an outsize place in the popular imagination. Their appeal is not unlike that of an action hero: they have outrageous levels of conviction and self-belief, but also a youthful earnestness and an obsession with impact that means you can’t help but root for them. There is some sense that the mere act of straying so far from established paths, at the age where they arguably exert the strongest pull, merits recompense; that anyone with the strength of character to do this is bound to be successful eventually. In other words, “great things come to those who won’t wait.”

Sitting in my postgraduate halls, a quick train ride from my childhood home, in early 2023, I had become quite the expert in waiting. The previous year, I’d only had one real ambition: to move to Paris to study the Cogmaster programme and deepen my understanding of computational cognitive science. When I was rejected, I told myself that I wasn’t ready. No one would accept me onto a technical postgraduate track - or indeed, a technical career path - with a degree in Linguistics. I had to wait until I had earned the required credential - which meant putting on hold my dream of living abroad, my interest in cognitive science, and the start of my career.

Predictably, this was a terrible idea. And so I found myself on the Eurostar one February morning, rereading my undergraduate thesis - my proudest achievement - and mulling over how best to present myself as an ‘outlier.’ Like many concepts that influenced my thinking over the past year, the importance of being an outlier is lifted straight from the ideology of Entrepreneur First, an incubator programme which recruits individuals rather than established teams and mentors them as they find a cofounder, build a product, and pitch for seed funding. When recruiting these individuals, they look for people with unusual drive and achievements relative to their peer group: people who learn things they’re too young to learn or aim for things they aren’t supposed to aim for. The essence of the dropout founder, if you will.

In my disillusionment, I was all too ready to channel this essence. Yes, founding a startup had been a vague ambition of mine ever since I got my first startup job in 2021. But what I really wanted was to stop waiting. I had spent 5 months in my home city, working through contrived coding assignments on topics I didn’t care about, feeling that my work had no impact on anything. So what I wanted was to move abroad, work directly on a problem I cared about, and have some impact on the world. I wanted to break free from the passivity into which I felt I had sunk - and what could possibly be more active than becoming a dropout founder?

With these thoughts bubbling in my mind, I dropped out of my master’s and joined Entrepreneur First. It was ironic that I chose France as the country to move to when I wanted to stray from established paths: France, land of the bac+5, where star entrepreneurs would sooner spend 7 years after high school on an entrepreneurship master’s track than drop out of university. On multiple occasions, I found myself wishing I had the financial stability to truly enjoy being in France and to build a more permanent life there. I noticed that for the most ambitious entrepreneurs in my cohort, such concerns never crossed their mind. Everything they did was for their future startup.

I also noticed that during my 6 months on the Entrepreneur First programme, I went from dropout founder to model student. Programmes like Entrepreneur First are among the more structured ways to explore entrepreneurship; it’s up to each individual to figure out how best to use their time, but there are a whole host of principles and precepts about successful entrepreneurship to guide them on their way. There was an Entrepreneur First-approved method to work out what problem to solve, who to solve it with, whether customers would pay money to have it solved. Of course, the methods weren’t gospel; they were simply a model based on the distribution of successful startups which the Entrepreneur First team had worked with. But whenever I was presented with a method or framework, I grasped it with both hands. I didn’t have the confidence - either in my own ability to found a company or in the ideas I had - to decide when I had something going for me which the model didn’t account for.

One enduring perception of the dropout founder is that their ignorance is their strength. A devtools founder whose experience comes from high school evenings tinkering with homemade apps, instead of 10 years of establishmentarian sprints, standups and scrum mastery, is likely to have unusual and refreshing perspectives on engineering, which they can then use to their advantage. I was never entirely comfortable with capitalising on my own ignorance. From the very start, my selling point - or my ’edge’, in Entrepreneur First parlance - was supposed to be my background in cognitive science. I was interested in using what I knew about behavioural science to optimise learning and communication processes. I sold myself as a generalist co-founder: someone with experience in sales, product management and software engineering, whose strengths lay in intellectual versatility rather than domain knowledge.

To my past self’s credit, this description of my strengths and interests is one that I would still use, and I managed to translate it into a few startup ideas I was genuinely passionate about. So I was decent at using what I knew, and what I was good at, to my advantage. But this was not good enough. My main lesson from the whole experience is this: what you don’t know provides as much of a competitive advantage as what you do. Dropout founder or not, there will inevitably be occasions on which your ignorance appears to bottleneck you as a founder. Maybe you’ve identified a problem and want to build a solution for it, but when you talk to potential customers, they don’t bring up this problem of their own accord. Maybe you work well with a potential cofounder, but neither of you have deep engineering expertise - or deep knowledge of the market you’re trying to enter. I was in both of these situations - and even if I hadn’t been, I would undoubtedly have run into some other problem which my prior expertise did not immediately equip me to solve. This goes for everyone, even former AI PhDs and McKinsey partners. What sets apart the founders who fail and the founders who succeed - what set me apart from my batchmates who are off to San Francisco to raise their seed rounds as we speak - is how they respond to the unknown.

And what struck me about the founders who succeeded was their confidence. Sometimes this confidence was distinctly establishment-bred. Several of the most impressive founders in my batch were far from dropouts; they were late-twenties MBA graduates with the poise and polish indicative of an adulthood spent entirely in Tier One schools and companies. Yet equally often, it stemmed from a profound belief in a particular vision of the future. The founders with this confidence maintained a careful balance between following the methods Entrepreneur First taught us and building out their own creative vision. When confronted with their own ignorance, they didn’t need to run to the safe shores of the rulebook and crumble when it appeared to invalidate the path they were following.

I, however, did. You might be wondering what I did when customers weren’t immediately on the same wavelength as me regarding my hypothesised problem, or when I felt that I worked well with a cofounder but my skillset didn’t entirely complement theirs, or when my market or technical knowledge were not perfectly suited to addressing a certain problem. Well, I abandoned all my efforts and went back to the drawing board. I was desperate to hyperoptimise everything I could while building a startup because I didn’t believe in my ability to make an imperfect startup work. I eventually realised that the bottleneck was my insecurity, not my ignorance. Of course, founder/problem fit and cofounder complementarity are important considerations, and Entrepreneur First were right to hammer them home. But to get the most out of a programme like Entrepreneur First (or really any advice you might get while founding a company) you need to be able to relativise whatever frameworks or approaches you encounter, and to decide when to embrace your own ignorance.

Although I was not able to do this, my foray into entrepreneurship has taught me an awful lot about myself and what I want. For now, my focus is on building my own confidence, maturity and vision through my new career in VC, and having conversations with people whom I could learn a thing or two from on that front. Entrepreneur First advised us to be the most ambitious versions of ourselves - and while doing so didn’t lead to me founding a company, it completely reshaped my goals for the near future and gave me a new perspective on life. You could call it dropout founder character development.

Slavophilia and Socialist Realism

![]()

Written in 2019, in my past life as an aspiring modern languages degree candidate.

While much of Europe spent the 19th century reshaping its systems of political and economic organisation, an intense intellectual debate in Russia was redefining the very nature of Russian-ness. The legacy of rulers like Peter I and Catherine I, who were responsible for modernising Russia’s courts, overhauling its army and dramatically increasing its foreign influence and artistic prowess, was deeply divisive. Although both of these rulers presided over usually popular developments – most notably military victory during the Great Northern War and Russo-Turkish wars – some of the most striking examples of their repressive leadership were their responses to those who challenged their progressive agenda, including the suppression of the Streltsy Rebellion1 and of around 160 popular uprisings between 1762 and 1772.2 In Russia, modernity did not always seem to have positive connotations.

This battle between decidedly forward-thinking rulers and a vocal chunk of the population who opposed them formed the backdrop against which the Slavophile tradition was born. In contrast to the group of intellectuals known as Westernisers, who, in Riasanovsky’s words, embraced Peter I as “the victorious creator of the Russian empire and its might, the sage organizer of the state, the lawgiver of modern Russia"3, the group who identified themselves as Slavophiles believed that his reforms were at odds with Russia’s fundamental character. They were prompted to become more vocal in civil discourse by Peter Chaadaev’s controversial Philosophical Letters, published in 1829,* in which he wrote (of Russia):

Isolated in the world, we have given nothing to the world, we have taught nothing to the world; we have not added a single idea to the mass of human ideas; we have contributed nothing to the progress of the human spirit.4

For Chaadaev, Russia’s isolation from the West was to blame for its lack of meaningful progress; “[Russians] have never moved in concert with other peoples” and so “the universal education of mankind has not touched us.”5 The Slavophiles’ response was that realising this separation from Western Europe by establishing a form of social organisation based on their own traditions was exactly what would improve Russia, rather than seeking to imitate a foreign model.6 They regarded the West as decadent and morally inferior; to them, Western people “were guilty of a multitude of sins. Egoism, communism, rationalism, sensuality, pride, affectation, superficiality, cruelty, bellicosity, exploitation, luxury, deceptiveness, rapacity, treachery, lechery, corruption, and decay were among “Their” attributes.”7 Given that communism was included in this list of sins, it might seem obvious that socialist realism cannot be considered part of the Slavophile tradition. To Slavophiles, socialist realism would have been viewed as a product of Western thought due to its aim of promoting communist ideology – indeed, Solzhenitsyn did criticise communism as the imposition of an alien, Western system on Russia.8 Meanwhile, socialist realists thought of their work as a new stage in artistic evolution – just as communism was a new stage in societal evolution – as opposed to the return to traditional ways championed by Slavophiles.9

On the other hand, we have already seen one similarity between the two schools of thought: the socialist government, and therefore the artwork it sanctioned, shared the Slavophiles’ disdain for Western societies (in this case, because they were bastions of bourgeois capitalism). Moreover, according to Dobrenko, this disdain was part of a conservative, even nationalist desire to create a “properly Russian, egalitarian, pseudo- collectivist, anti-market, anti-bourgeois, anti-Western […] socialist utopia”10 which existed alongside support for rapid industrialisation and the notion of proletarian internationalism. Thus, even though socialist realism was supposedly an entirely new, revolutionary style of art distinct from previous ‘bourgeois’ art, running through its Russian incarnation were echoes of a century-old duality: the coexistence of a muted admiration of Western liberal technocracy and an instinctive repulsion by it. To examine this further, this essay will compare the key values and the portrayal of Russia and Russians which can be seen in the ideas of Slavophiles and socialist realists, in order to determine to what extent socialist realism was simply a red-tinted continuation of Slavophilia.

According to Slavophiles, the moral decay of Western Europe was rooted in its adoption of inferior forms of Christianity. Their opposition to Westernisation could in part be reduced to a belief that the Russian Orthodox Church had a special place in Russian history, and that emulating Western mores which were informed by Catholicism would corrupt the uniquely Orthodox character of Russia.11 In fact, any authority which attempted to place itself above the Church in the hierarchy of Russian society was automatically opposed by Slavophiles, including the government of Nicholas I – which, despite its official mantra of ’Orthodoxy, Autocracy and Nationality’, prioritised autocracy over orthodoxy and aimed to render the Church subordinate to the state.12 Immediately, the central position of religion in Slavophile ideas appears to set it apart from socialist realism; a movement with the goal of developing a secular, proletarian culture surely could not be part of a tradition with the goal of restoring the hegemony of religious authority. As well as this obvious difference in values, the reasoning behind Slavophiles’ opposition to Western styles of governance reveals another difference between them and socialist realists. The concept of moral decay is at odds with ’scientific socialism.’ Engels wrote in Anti-Dühring that:

“We therefore reject every attempt to impose on us any moral dogma whatsoever as an eternal, ultimate and forever immutable ethical law on the pretext that the moral world, too, has its permanent principles which stand above history and the differences between nations. We maintain on the contrary that all moral theories have been hitherto the product, in the last analysis, of the economic conditions of society obtaining at the time. And as society has hitherto moved in class antagonisms, morality has always been class morality; it has either justified the domination and the interests of the ruling class, or ever since the oppressed class became powerful enough, it has represented its indignation against this domination and the future interests of the oppressed.”13

Socialists therefore support the furthest thing possible from a permanent religious authority whose close relationship to Russian identity gives it an unquestionable right to the highest power in Russia. They reject any idea of morality on the grounds that it necessarily reflects ruling class ideology, and so for them, the defects of Western systems of government do not lie in an inherent moral corruption but in the specific class antagonisms within those systems at a certain point in time.

While not based on ethical propositions, however, socialist criticisms had another “objective” basis: the historical materialist theory of social history. Dialectical and historical materialism are characterised by their rather bold claim to have formulated a set of laws by which societal development invariably unfolds. Tellingly, in his 1938 publication Dialectical and Historical Materialism, Stalin (socialist realism’s biggest sponsor) stresses the ostensibly objective and scientific nature of the theory, referring multiple times to the ‘laws’ of social history and the idea that “the science of the history of society can become as precise a science as, let us say, biology”14 (italics added). That Russian socialists were so quick to embrace the purported objectivity of Marxist analysis suggests that they had an appetite for such objectivity, and sought scientific justification for it in the absence of religion. Slavophiles’ advocacy of the supremacy of religious authority based on unchanging cultural and ethical values represented a deep-seated conservative morality; socialist realists, although they replaced this authority and these values with ’progressive’ ones, retained their veneration of the immutable.

The subject of authority is another area with more commonalities than there initially seem to be. Both Slavophiles and socialists are associated with authoritarianism, but their attitudes towards authority are more nuanced and contingent than blindly reverential. In Slavophile thought, an ideal Russian state would use autocratic methods to enforce traditional values. However, any state which did not uphold truly Russian principles would be viewed with suspicion by Slavophiles, who believed that authoritarianism was often connected to the imposition of alien values on the Russian people.15 This was the kernel of their aforementioned dispute with Nicholas I, a ruler who superficially shared many of their values. Socialist ideology likewise does not contain the slightest hint of unconditional respect for authority. On the contrary, it encourages insurrection against oppressive bourgeois governments, of the sort that Stalin’s government funded (most significantly through their backing of the PSUC during the Spanish Civil War) and ultimately supports a society in which the state has ’withered away.’ Both Lenin and Stalin made it very clear that although the end goal was a stateless society, a strong proletarian state would be desirable. As Lenin wrote (and Stalin quoted):

“The dictatorship of the proletariat is the rule—unrestricted by law and based on force—of the proletariat over the bourgeoisie, a rule enjoying the sympathy and support of the labouring and exploited masses.”16

In addition, “the dictatorship of the proletariat does not differ fundamentally from the dictatorship of any other class.”17 Therefore, just as the bourgeoisie or nobility coercively suppressed other classes under capitalism and feudalism, the proletariat would do the same and be justified in doing so. Slavophilic conditional authoritarianism shows why this view of authority might have been easy to digest in Russia; Russians were used to the basic notion that autocracy was not inherently preferable, but the right kind of autocratic government was worth respecting.

Socialist realist art put this take on authority into practice during Stalin’s premiership. A lesser-known conflict between Slavophiles and Westernisers during the 19th century concerns how to bridge the divide between elite and mass culture: Westernisers maintained that the intellectual level of the masses needed to be raised to that of the intelligentsia, whereas Slavophiles favoured simplifying literature to ‘bring it to the people.’18 The intention of socialist realists was not to bridge this divide, but to transcend it.19 This implies a different sort of discontinuity between Slavophilic and socialist realist ideas: as socialists might have argued, the reason behind the reproduction of certain Slavophile ideas in socialist realism could be the sublation of pre-socialist debates entailed by the proletarian revolution, which would mean that socialist realism is part of a new tradition with a few lingering vestiges of the culture which preceded it. However, socialist realists employed a particular top-down style of stimulating mass cultural engagement which had more than a little in common with the Slavophilic populist-authoritarian hybrid.

The first similarity between the two relates to the regulation of artistic expression in the Soviet Union under Stalin. The picture we often have in the West of the arts in the Soviet Union is one of tightly-controlled, Marxist conformism, where every brushstroke and every comma must sing a song of eternal proletarian glory. Of course, there was censorship and a certain degree of partiinost’ to which the cultural intelligentsia had to conform, but since artists were not required to be party members, the orthodoxies of pre- Soviet art and literature were allowed to filter through into socialist consciousness just as socialist values filtered into the work of the former ‘bourgeois’ intelligentsia. Rather than being dominated by Marxism, creative output under Stalin was dominated by an overarching conservatism, which gave artists immense impetus to conform not only to the orthodoxy of socialist realism but also to imitate the artists of the past who were afforded the greatest respect: Pushkin in poetry, Stanislavsky in theatre, the Itinerants (19th century Russian realists) in painting.20 Thus, although one of the stated objectives of socialist realism was to create a new art style which was accessible and relevant to workers,21 they did so by appealing to traditional Russian artistic convention and strongly promoting conformity to it. The restrictive environment which came to exist as a result bore little resemblance to the revolutionary futurism which flourished immediately after the 1917 revolutions, and seems more like the return to tradition welcomed by Slavophiles.

The second similarity lies in the innate authoritarianism of the art style itself. As Stalin consolidated his grip on power, the fourth tenet of socialist realism agreed on at the Congress of 1934 – portraying the Communist Party of the Soviet Union and its mission in a positive light22 - increasingly developed into the near-deification of Stalin as a person. A famous example is Under the Banner of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin, created by Gustav Klutsis in 1935 using photomontage:

This poster contains many of the defining features of socialist realist art. The background is an unmistakeably industrial setting divided into four sections, of which the first three show struggle and revolution, while the fourth shows a crowd of beaming workers, appearing to be marching forward. Photomontage has been used to superimpose the heads of Marx, Engels, Lenin and Stalin onto the scene, on a red banner, as if they were watching over the victorious workers below them. The symbolism of the chimneys and the crowd are obvious: the poster is heralding the victory of the industrial proletariat and emphasising the collective nature of class struggle and progress towards communism.

This is not an image of perfect equality, though. The depiction of the four Marxist leaders is typical of the artistic methods used to foster Stalin’s personality cult: their positioning above the crowd and at the centre of the image gives the impression that they are to be respected, and out of the four, Stalin stands out for being the only forward-facing head. The other three leaders are looking in his direction, as if looking towards the communist future he represents, and directly beneath his gaze is a large group of workers unified by their smiling faces and their implied forward motion. This poster is not about the proletariat as a whole, or the revolution as a whole, or the goal of a free and equal society; it is about the line of great communist leaders whose climax was Stalin, and how Stalin continued and deepened the legacy of his predecessors by ensuring the happiness of the masses pictured below him. In other words, this poster is a paean to authority. Ironically, socialist realists’ efforts to create a proletarian culture involved more conservatism and more leader-worship than ever, bringing to mind the peculiarly authoritarian brand of populism so beloved of Slavophiles.

The final aspect of this comparison between Slavophiles and socialist realists is the ends of each movement: the kind of society, and indeed the kind of individual, which Slavophiles and socialist realists strove to form and regarded as the pinnacle of human capability. Even in this area, there appear to be some glaring similarities between the ideologies. As ever, the ideal society envisaged by Slavophiles displays a characteristic ambiguity concerning the question of the state. The original Russian method of sociopolitical organisation, free from any Western influences, was said to have been a harmonious, co-operative and peaceful peasant commune (mir or obshchina), in which there existed no coercion and “a natural and moral fraternity [among Russians].”23 A lack of coercion, of course, implies the lack of a state apparatus. This anarchistic concept of a network of stateless, freely- associated communes defined by their Russian quality is not dissimilar to the communist vision. Marx and Engels describe the formation of a society without political power in The Communist Manifesto:*

“When, in the course of development, class distinctions have disappeared, and all production has been concentrated in the hands of a vast association of the whole nation, the public power will lose its political character. […] In place of the old bourgeois society, with its classes and class antagonisms, we shall have an association, in which the free development of each is the condition for the free development of all.”24

It is important to note that this society without class distinctions was theoretically the aesthetic ideal of socialist realism, given that one purpose of socialist realism was to provide a positive, hopeful depiction of the direction of social progress.25 Even the nationalism of the Slavophiles’ outlook, which prized communal organisation by virtue of its Russian-ness, could be seen to some extent in socialist realist doctrine. Art was required to be “national in form, Socialist in content”, particularly after World War 2, when patriotic allegiance to the Soviet Union was combined with allegiance to the communist mission in order to win over citizens of the new Eastern Bloc.26

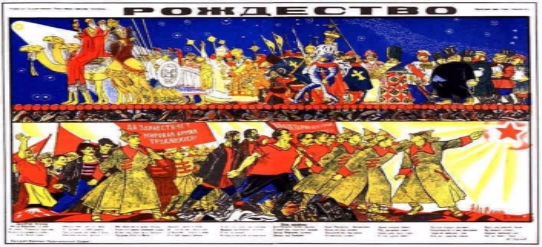

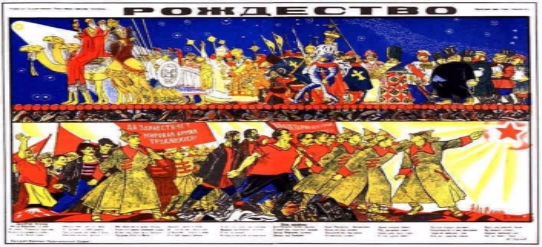

The motive of winning people over provided much of the impetus behind the cultural recycling responsible for socialist realism’s conservative undertones. Cultural recycling is the process of imbuing familiar symbols with new meanings, to communicate a new idea using symbols which already have positive associations. Often, socialism was the new idea, while Orthodox icons were the familiar symbols. Dmitry Moor’s Christmas (1921) is an example:

Moor was firmly on the realist side of the realism vs. abstraction debate of the early 1920s, and as well as exemplifying early realism, this poster clearly uses traditional Russian symbolism. Transfiguration, in Russian Orthodoxy, involves a halo or rays of light shining down on a person or object to bestow divine sanction upon them, and is evoked by the depiction of light rays shining down on the field. As transfiguration represents divinely-sanctioned legitimacy and the sun represents salvation through Christ, the red star placed (tellingly) over the sun and the rays it emits represent salvation through revolution and the blessing given to workers to carry out their ‘holy’ mission. Due to cultural recycling, many quintessentially Russian motifs were incorporated into socialist realism, giving it – in a sense – the Russian-ness to which Slavophiles aspired. Though such similarities exist, for the most part, the idealised society of socialist realist art was not a descendant of the Russian peasant commune. Socialist realism gives an impression of rigidity, of having one constant party line which must always be followed, and this makes it easy to forget that this art movement is laden with contradictions - as the ideas of its originators frequently were. Though the Communist Party did promote ‘Russification’ in the 1930s, seeking to unite the disparate nationalities within Soviet borders under a common, Soviet identity and language as war approached, it was always careful to distance ‘Soviet patriotism’ from the bourgeois Russian nationalism it roundly condemned. Russians were not praised for their innate spiritual purity, but for having led the international proletariat by carrying out the first revolution.27 The hope was that the rest of the global proletariat would join the Russians to form an international communist society, and when this happened, Russia would not be superior in any way. Unlike Slavophilic patriotism, this patriotism was transient, with the pursuit of international ends in mind.

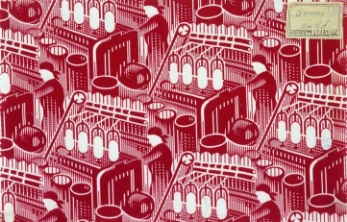

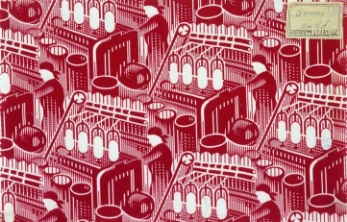

Moreover, far from creating backward yet wholly Russian peasant communes, Soviet leaders desperately wanted to bring their country in line with the industrialisation levels of Western Europe. The ideal Soviet citizen was not a peasant, but an industrial proletarian, working hard to make his country more modern and productive.28 Socialist realism reflects this appetite for modernisation using romanticised industrial settings. The poster below (left), Help Build the Gigantic Factories (Mirzoyan and Ivanov, 1929), advertises the first Five Year Plan and the heavy industrialisation it called for by portraying industry as beautiful and its construction as a glorious, collaborative effort. Industrial imagery was even used on fabric prints such as Golubev’s Red Spinner (right), designed in 1930.

The depiction of industry and technology as not only necessary but beautiful shows how central it was to the socialist realist worldview. This contrasts sharply with Slavophiles’ idealisation of peasant-based societies. Although they opportunistically employed Russian and Orthodox imagery, the society socialist realists strove to create was technologically-advanced, modern and highly efficient, sharing more similarities with the European societies loathed by Slavophiles than with any peasant commune.

It is undeniable that, for all its modernising rhetoric, an idealistic, nationalistic conservatism comparable to Slavophile nostalgia was present in socialist realist thought. However, the opportunistic way in which this conservatism was used to entice formerly religious and patriotic workers, rather than out of any true fidelity to Orthodoxy, advocacy for peasant causes or belief in the inherent supremacy of Russian-ness, indicates that Slavophiles were never truly their ideological progenitor. The relevance of this essay does not come from unearthing a hidden fraternity between two ostensibly opposed schools of thought, but from noting that quasi- Slavophilic ideas have had a unique allure to Russians for centuries. In the 21st century, as an oddly familiar brand of insular traditionalism is used to drum up Russian support for interventionism abroad and autocracy at home, understanding these ideas is the key to understanding Russia itself.

-

Jeremy Black, War: a short history, (London:* A&C Black, 2014), 83 ↩︎

-

Yury V. Bosin, “Pugachev’s Rebellion, 1773-1775,” The International Encyclopedia of Revolution and Protest (New York: Blackwell Publishing, 2009), 1-3 ↩︎

-

Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, _The Image of Peter the Great in Russian History and Though_t (New York: Oxford University Press, 1985), 304 ↩︎

-

Peter Chaadayev. “Philosophical Letters,” in Teleskop, Vol 1 of _Russian Philosoph_y, ed. James Edie (Knoxville, Tennessee: University of Tennessee Press, 1976), 116 ↩︎

-

Ibid, 90 ↩︎

-

Guerman Diligensky and Sergei Chugrov, “The West” in Russian Mentality (Moscow: Brussels Institute of World Economy and International Relation_s_, 2000), 7 ↩︎

-

Nicholas V. Riasanovsky, Russia and the West in the Teaching of the Slavophiles: A Study of Romantic Ideology (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1952), 91 ↩︎

-

David G. Rowley, “Aleksandr Solzhenitsyn and Russian Nationalism,” Journal of Contemporary History vol. 32 no. 3 (1997): 323. url: https://www.jstor.org/stable/260964 ↩︎

-

Andris Teikmanis, “Toward Models of Socialist Realism.” Baltic Journal of Art History no. 6 (2013): 98 ↩︎

-

Evgenii A. Dobrenko, Political Economy of Socialist Realism (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 2007), 33 ↩︎

-

John D. Basil, ”Alexander Kireev : Turn-of-the-century Slavophile and the Russian Orthodox Church”, Cahiers du monde sovietique, vol 32, no. 3 (1991): 338. doi: https://doi.org/10.3406/cmr.1991.2285* ↩︎

-

Laura Engelstein, ”Holy Russia in Modern Times: An Essay on Orthodoxy and Cultural Change”, Past & Present no. 173 (2001): 138 ↩︎

-

Friedrich Engels, Anti-Dühring: Herr Eugen Dühring’s Revolution in Science (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1947). https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1877/anti-duhring/ ↩︎

-

Joseph Stalin, Dialectical and Historical Materialism (Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1938) https://www.marxists.org/reference/archive/stalin/works/1938/09.htm ↩︎

-

Victor Terras, Handbook of Russian Literature (New Haven, CT: Yale University Press, 1985), 423 ↩︎

-

Joseph Stalin, Leninism: Volume One (Moscow: Foreign Languages Publishing House, 1950), 287 ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Irina Gutkin, The Cultural Origins of the Socialist Realist Aesthetic, 1890-1934 (Evanston, IL: Northwestern University Press, 1999), 73 ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Sheila Fitzpatrick, ”Culture and Politics under Stalin: A Reappraisal”, Slavic Review vol. 35 no. 2 (1976): 223 ↩︎

-

Dubravka Juraga and Keith M, Booker, Socialist Cultures East and West (Westport, CT: Praeger, 2002), 68 ↩︎

-

Ibid. ↩︎

-

Gary M. Hamburg and Randall A. Poole, A History of Russian Philosophy 1830-1930: Faith, Reason and the Defense of Human Dignity (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 33 ↩︎

-

Karl Marx and Frederic Engels (trans. Samuel Moore), Manifesto of the Communist Party (Moscow: Progress Publishers, 1969). https://www.marxists.org/archive/marx/works/1848/communist-manifesto/ch02.htm* ↩︎

-

G. Žekulin, ”Forerunner of Socialist Realism: The Novel ’What to Do?’ by N.G. Chernyevsky,” The Slavonic and East European Review, vol. 41, no. 97 (1963): 469 ↩︎

-

Jerome Bazin, ”Socialist Realism and its International Models,” Twentieth Century History Review, vol. 1 no. 109 (2011). doi: 10.3917/vin.109.0072 ↩︎

-

Andrei Shcherbakov, ”Nationalism in the USSR: a historical and comparative perspective”, Nationalities Papers, vol. 43 no. 6 (2015): 879. doi: 10.1080/00905992.2015.1072811 ↩︎

-

Peter Fritzsche and Jochan Hellbeck, Beyond Totalitarianism: Stalinism and Nazism Compared (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2009), 315 ↩︎